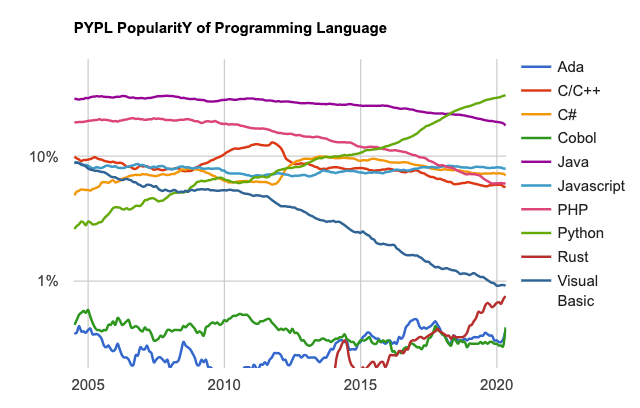

Based on the data collected by PYPL and shown in the chart below, over the last 5 years, PHP and Java declined in popularity while Python’s popularity rose. Sometime in 2018, Python became the most popular language. But Python probably won’t be #1 forever. If history is any indication, no language can maintain the premier position in language popularity indefinitely. I’m sure there were many who believed that Java would never be replaced as #1.

(Image source: PYPL)

But that certainly does not mean that Python is going away completely. Virtually none of the languages that have come to prominence in the past have disappeared yet. They continue on as legacy code. Looking at the bottom right of the same chart, we see that people are still learning to code in Cobol and Ada. The last Cobol programmer on the planet will probably be the highest paid programmer on the planet. We also see that a newcomer, Rust, is quickly climbing the chart. Will it be the new #1 someday?

So the questions more relevant than “will Python stay #1 forever?” are: “when will Python fall out of prominent use?,” “why?,” and “should we care?”

I’ll take the “should we care?” question first. When a new language comes to prominence, sometimes it is addressing an entirely new need. In those cases all the work of creating software in the language is new and the value is additive so there is no real cost to the industry driven by the emergence of a new language. In most cases however, there is some overlap between the applications of the new language and existing languages. When there is overlap, that means that work needs to be done to convert code from the old language to the new or to do integration between the old and new languages. This costs time and money. Re-training developers to use the new language is also a significant cost. When you consider the amount of money the world puts into software every year, even a partial overlap between the old and new prominent language can represent billions of dollars. So the answer to “should we care?” is “yes”. For the software industry—and any industry that uses software—transitions in languages are costly. For individual developers it can mean potential skill obsolescence. In this sense it would be best for everyone if the current top languages could dominate forever. But that has never happened yet.

The question of “when” Python will decline is really impossible to answer with any precision. It is hard to say when a new language or application will cause Python to start its descent into obsolescence. One thing we can say is that the transition will not be quick.

There is a great deal of momentum to a prominently used language. There is the momentum of the code in many applications that have cost billions of dollars to create. If those applications are still doing their job, they will not be rewritten until they no longer work.

Then there is the momentum of libraries that have been written to extend a language. Python is unusual in that it has a relatively small language core supplemented by additional code to add functionality. Its creator, Guido van Rossum, intended it to be a highly extensible language meaning that libraries could be easily written to extend its core functionality into many domains. And that has happened in a big way. A huge community of developers have written libraries to add functionality to the Python core. These libraries range from machine learning, to visualization, database access, web applications, and the list goes on. The official repository for Python third party libraries, PyPi, now contains over 230,000 libraries. Again, these represent billions of dollars of investment that will take time to replace even if the incentive to change is strong.

And finally there is the momentum of the talent base. Inevitably, when there is a new “hot” language coming to prominence, there is a shortage of experienced developers. All this means it takes time to transition from one language to the next no matter how strong the benefits of changing are.

The question of “why” Python will eventually fall from prominence will be because either it has some shortcomings that a new language fixes or there is a new application that Python is not suited to perform efficiently. Again it is impossible to predict the new application that will obsolete existing languages. It’s much easier to discuss the strengths that led to the Python’s popularity and to also consider the weaknesses in Python that could open the door for a new language.

The strengths of Python are well-known: its readability and dynamic typing led to its rapid adoption by domain experts in many fields, its extensibility led to the creation of many, many libraries that brought even more users, and its diverse and global community has led to a robust foundation enabling contributions from anyone.

The weaknesses of Python are also well documented. The item that often tops the lists is Python’s speed. Python is an interpreted language meaning that, unlike compiled languages, the human written code is converted (interpreted) to machine executable code at the time of execution rather than ahead of time (compiled). This interpretation step means that runtime speed is lower than compiled languages.

Another attribute of CPython (the most widely used implementation of Python) that is often cited as a weakness is the GIL or Global Interpreter Lock. In an age of massive hardware parallelism (such as GPUs with thousands of hardware cores), a per-interpreter lock means that only one thread (of CPython bytecode) can execute at the same time. This means that certain patterns of concurrency are not well suited for the Python interpreter. Python developers have found ways to address both the speed and concurrency (or scaling) limitations of the interpreter. Python is an extensible language meaning that you can access code written in other languages from within Python code. Developers take advantage of this to speed up python by writing compute intensive algorithms in a compiled language like C. These compiled segments of code can run on many cores and on GPUs where they look to the Python interpreter as one compute-heavy instruction. There are even solutions like Cython and Numba that make it easy to use Python syntax to create compiled code, and therefore, compiled language performance from a Python program.

However, the common methods of getting speed and scale into your Python run-times are implementation dependent meaning that you have to commit to a certain underlying runtime solution for Python such as CPython. Your Python code is no longer portable to other, incompatible Python runtime implementations paradigms such as PyPy, Jython (Java), IronPython (.NET), MicroPython (IOT), and Brython (web).

Portable performance and scale are Python’s achilles heel. It has other weaknesses but these are the ones most likely to open the door for another language to replace Python. So we should be keeping our eyes out for languages with all (or most) of the benefits of Python without the portable performance limitations as the signal that Python is on its way out.

Or we could figure out better ways to add portable performance and scale to Python…but that is the subject of a future post.